“Will the bitter battles that arise from the strong preying upon the weak ever be banished from this earth?“

- Original Title: 仁義なき戦い

- Directed by: Fukasaku Kinji

- Featuring: Sugawara Bunta, Kaneko Nobuo, Kobayashi Akira, Umemiya Tatsuo, Tanaka Kunie, Ibuki Gorō, Matsukata Hiroshi & more

- Studio: Toei

- Extras: Plot Deep Dive [1] | Review [1] | Plot Deep Dive [2] | Review [2] | Plot Deep Dive [3 Part 1 – Part 2]

Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a complex saga that can be difficult to get into for a variety of reasons: context, genre tropes and cinematography, sprawling cast, labyrinthine plot… But the journey is worth it – so to start on the right foot (or as an incentive to get back into it), here are five keys to get started with the five-part yakuza epic. No spoilers!

KEY 1: Context & History

Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a story spanning 24 years, and charting the rise and fall of various Western Japan yakuza families from 1946 onwards. It’s also a series anchored in the historical events that shook the period, used by the director as framing points for the viewer to understand the context of the characters’ fortunes and actions. The title sequence of the first film opens with the Hiroshima atomic bomb, followed by images of the devastation and poverty that ensued, before dropping us in the Kure (Hiroshima) ramshackle black market to meet our characters. The characters’ proximity to such violence, and their obvious lack of prospects, goes a long way to contextualise their criminal path.

The subsequent films’ opening sequences link further events to the ebbing fortunes of the yakuza: the Korean War brings lucrative contracts and even tighter political links; the Cold War and Japanese political events mirrors the proxy wars and chaos of the yakuza world of the time; the Tokyo Olympics and opening of Japan to the world turn the unruly the yakuza into pariahs, subject to drastically increased police scrutiny. (see KEY 5 for all dates and context)

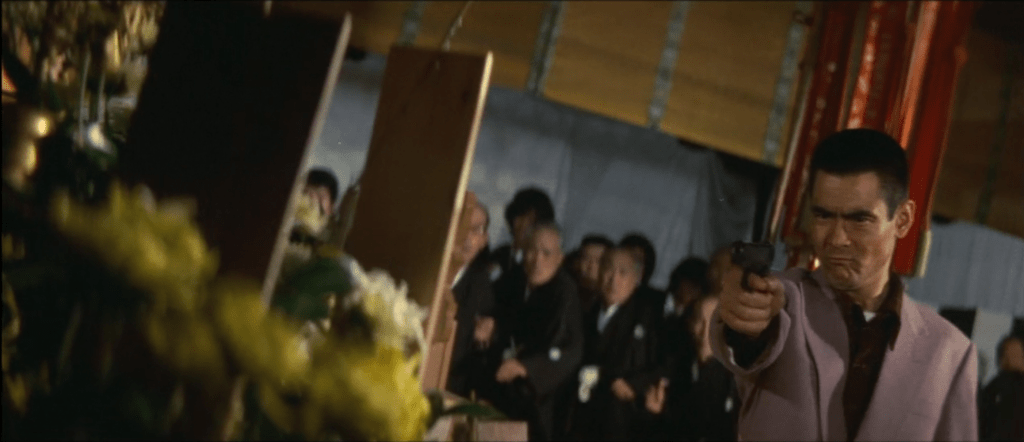

On a lighter note, as time (and the series) evolves, so do the characters’ appearance: army clothing gives way to muted suits, before exploding into bold, expensive fashion. Note the characters’ accessories and glasses – often blue or light brown-tinted, a staple of the fashion-forward yakuza. With new wardrobes also come fancier hang-outs, restaurants, bigger bars, bigger cars – all the signs of success that reflect their ascension in the world and in the ranks of the yakuza world. They might die at the drop of a hat, but it will be a fashionable one.

KEY 2: The Jitsuroku Masterpiece

After a decade dominated by ‘ninkyo’ (chivalrous yakuza) films and some borderless action (Nikkatsu’s mix of occidental cinema and Japanese sensibilities), the troubled social climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s Japan demanded something different from the genre – and ‘jitsuroku’ (true account) filled that gap, with Battles Without Honor and Humanity at its helm. Gritty, dynamic, grim, often based on true crime, jitsuroku eschew all forms of chivalry and instead portray yakuza life in all its pettiness and violence, with violent thugs, anti-heroes, and scheming bosses having it out between two messy gun fights – even using local dialects for authenticity (here, Hiroshima dialect).

Based on a the memoirs of real-life yakuza Kōzō Minō, and with plenty of yakuza to advise the cast and crew1, Battles Without Honor and Humanity also offered the most realistic portrayal of yakuza life to date, greatly enhanced by pioneer director Fukasaku’s wild, guerilla filming style (see KEY 3). The push for realism went as far as filming in streets and train stations without any authorisation, leading to civilian panic and outcry from local authorities2. The Battles actors only added to the tension by occasionally hitting each other for real by accident3, and by seriously endangering themselves in elaborate stunts3.

KEY 3: Fukasaku, the Maverick Director

On first watch, Battles Without Honor and Humanity’s visuals can be disconcerting. Characters are introduced (and killed) at a dizzying pace, with character information relayed through screen overlays that are often the viewer’s only chance to register it. A few voice-overs explain key context and events, but the rest is firmly up to the viewer to remember and analyse. However, this impression of general chaos (which can absolutely be enjoyed as is, ideally with a strong bottle of sake) hides very methodical and precise beat-by-beat storytelling with neatly organised thematic chapters, detailed and consistent webs of relationships, and never a wasted scene or character. The more you piece together, the more astonishing the orchestration of events is – so much, into such relatively short (99 too 119-minute) runtimes.

The attention to detail carries into the filming methods. The famous Fukasaku “shaky camera” used in action scenes highlights the messiness of killing done by men who are professionals only by name: missed opportunities, lethal pausing, endless bullets missing the mark or hitting the wrong target, panicked yelling and rolling on the floor – professional hitmen they are not. But the camera also shines in the quiet moments. As is fitting of an ensemble cast film, characters are rarely alone in the frame, and even then are not always in clear view with props or other characters in the way. Using eye or shoulder-level shots, Fukasaku puts us in the room with the characters – and this proximity is not innocent. An incredible amount of detail is gleaned from watching all the characters: the subtle glances exchanged in the background, the expressions washing over a character’s face, the strange activities and actions they do away from the center of the screen. Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a show-not-tell film that seems to endlessly reward pausing and rewatches.

KEY 4: An All-Star Ensemble Cast

By the early 1970s, television was eating away at the cinema audiences and profitability. This shift led to difficult conditions for studios, with some driven to bankruptcy (Daiei), or opting to focus on 18+ productions (Nikkatsu). But this also meant new availability for their biggest stars, allowing Toei to contract the cream of the crop across several studios – such as Kobayashi Akira (playing Takeda) and Kaneko Nobuo (playing Yamamori) from Nikkatsu, or Narita Mikio (playing Matsunaga) from Daiei. Added to the existing Toei talent, these inclusions allowed Fukasaku to assemble a varied roster of actors at the peak of their craft for Battles Without Honor and Humanity, and to foster an interesting ensemble dynamic4. In Battles, even the recurring extras were best in class: dubbed ‘The Piranhas’, this group of bit-part actors and drinking buddies brought a unique energy to the series, livening up action scenes and even competing to see how could do the most over-the-top death scenes3.

But the sprawling story of the saga required even more roles than Fukasaku had actors – leading several actors to come back two or three times over the course of the series, each time with a different role and slightly different make-up.

KEY 5: Understanding the Series’ Structure & Characters

Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a story that spans 24 years (1946-1970), told over five episodes (initially 4, before Toei asked Fukasaku to add one more to the extremely successful series). While the episodes are mostly sequential, with the exception of Episode 2 which occurs at the same time than Episode 1, it’s interesting to note that the series shifts in tone and focus over the course of the five films:

- Episode 1:

- Years: 1946-1956

- Key Event: Hiroshima Atomic Bomb / recent end of WWII

- Focus: Yamamori family (vs Doi, vs itself) / Hirono Shōzō

- Theme: formative years of the Yamamori family and Hirono Shōzō

- Episode 2:

- Years: 1950-1955

- Key Event: Korean War

- Focus: Muraoka family / Yamanaka Shōji vs Otomo family / Otomo Katsutoshi

- Theme: contrasting characters of the new generation (side story, with many links to main story)

- Episode 3:

- Years: 1960-1963

- Key Event: Cold War, tense Japanese political climate

- Focus: merging of Yamamori / Muraoka families vs Akashi family

- Theme: contested M&A and preparation for large-scale conflict

- Episode 4:

- Years: 1963-1964

- Key Event: 1964 Tokyo Olympics

- Focus: pro-Yamamori families vs pro-Akashi families

- Theme: large-scale conflict, police interference

- Episode 5:

- Years: 1965-1970

- Key Event: anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb

- Focus: Tensei coalition / Takeda Akira / his successor Matsumura Tamotsu (& various enemies)

- Themes: successes and failures of transforming the yakuza into political organisations, changing of the guard

- Note: the series originally ended after Police Tactics, but this final episode was made upon the studio’s request – and completes the story arcs of all main characters.

Getting a good grasp of key characters, their relationships, and their alignment (moral or organisational) can also be helpful to fully appreciate the subtleties of the alliances – and backstabs (see Plot Deep Dives for available character charts, including Battles Without Honor and Humanity 1 – and more coming soon).

In Conclusion

Battles Without Honor and Humanity is a deep, complex, and expertly crafted series, with a cast and crew at the peak of their artistry. Whether you embrace the chaos (strong sake advised) or slowly untangle all the machinations at play in this seminal jitsuroku yakuza saga, have fun on your journey – and beware of Yamamori!

Notes and References

1. As reported by Umemiya Tatsuo in Mark Shilling’s ‘The Yakuza Movie Book’, pp. 33-35

2. As reported in Battles Without Honor and Humanity: Hiroshima Death Match (Blu-ray, Arrow Films)

3. As reported in the Battles Without Honor and Humanity: Proxy War (Blu-ray, Arrow Films) mini-documentary ‘Secrets of the Piranha Army‘

4. As reported by Sugawara Bunta in Mark Shilling’s ‘The Yakuza Movie Book’, p.139

Discover more from Gamblers & Drifters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.