“I myself have always made films for entertainment; I believe that film is a spectacle. Arousing the spectator’s curiosity, dressing up the unreal to make it look real, fooling the spectator, that’s what a spectacle is all about.”1

With this quote, the free-thinking director introduces us to his unmistakable style: unhibited, imaginative, and with a unique theatrical touch that no others could match. Throughout the 1960s and beyond, Suzuki released a wide variety of films that chart his creative explorations, as well as his struggle to find freedom within the rigid Nikkatsu production system. Here are five classics big and small to explore Suzuki’s opus through time – and a note on his post-Nikkatsu career.

- THE WIND-OF-YOUTH GROUP CROSSES THE MOUNTAIN PATH (1961)

- DETECTIVE BUREAU 2-3: GO TO HELL BASTARDS! (1963)

- YOUTH OF THE BEAST (1963)

- TOKYO DRIFTER (1966)

- BRANDED TO KILL (1967)

THE WIND-OF-YOUTH GROUP CROSSES THE MOUNTAIN PATH (1961)

– THE COLOURFUL YOUTH FILM –

“I know that pessimism gets me nowhere. There’s enough trouble in the world.“

- Original Title: 峠を渡る若い風

- Featuring: Kōji Wada, Kaneko Nobuo, Shimizu Mayumi, Morikawa Shin, & more

- Studio: Nikkatsu

By late 1960, the reluctant director2 was gaining traction at his new studio Nikkatsu, and given the ultimate accolade: the ability to work with then-expensive colour film, and to cast Nikkatsu’s most successful and profitable actors, the Diamond Line (or Diamond Guys)3. Suzuki embarked on a series of collaborations with 17 year-old Diamond Line actor Kōji Wada (also lead actor in Suzuki’s charming Tokyo Knights (1961)), using the opportunity to develop the inventive cinematic flourishes that would soon become his trademark.

Amidst a backdrop of bright, colourful matsuri (local festivals, beloved by and lovingly filmed here by Suzuki), the relentlessly good-natured travelling student Shintaro (Kōji Wada) helps and befriends everyone on his path. From traveling with amused yakuza, to selling pants with a renegade gangster (played by the inimitable Kaneko Nobuo), to settling quarrels with paint fights, thumb matches, or marketing campaigns – nothing resists Shintaro and his infectious smile. Suzuki’s ability to transform simple stories into memorable spectacles is already at play in this festival of bold colours, unusual shots, and oddball humour. Suzuki later remarked that he greatly enjoyed making this film4, and it shows – watch on a warm summer day for a joyful example of the director’s fun side at play.

DETECTIVE BUREAU 2-3: GO TO HELL BASTARDS! (1963)

– THE DETECTIVE COMEDY –

“This isn’t some American TV show. We don’t need private detectives.”

- Original Title:探偵事務所 2 3 くたばれ悪党ども

- Featuring: Shishido Jō, Kaneko Nobuo, Kawachi Tamio, Sasamori Reiko & more

- Studio: Nikkatsu

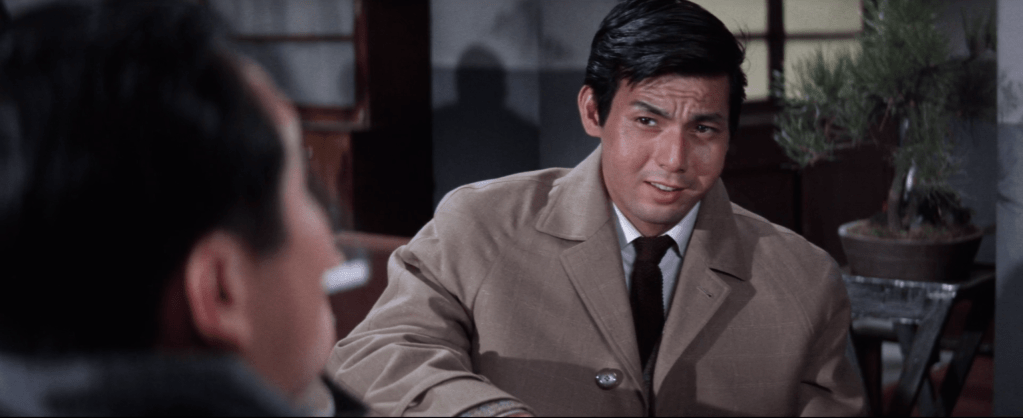

In 1962, slowly but surely reaching the peak of his career at Nikkatsu, Suzuki was reunited with an old acquaintance: Shishido Jō. Shishido, who started at Nikkatsu around the same time than Suzuki, also found himself on the up, hot on the heels of filming a Nikkatsu western in Mexico with a broken leg5 and given another lead role in an expensive detective film – all in colour. A boon for the self-professed #1 fan of Hollywood noir6.

In a studio system where directors were expected to take on any assignment they were given7, individuality could make a big difference – as demonstrated by this whacky collaboration between the two eccentrics. Faced with a pedestrian story of revenge, yakuza wars, cheeky detectives, and infiltration, Suzuki and Shishido go all out on the detail. Suzuki’s splashes of colour, audacious shots, dark/self-referential comedy, and yakuza raids conducted to the sound of chirpy jazz are the perfect backdrop for an equally chirpy Shishido, bouncing from to an impromptu song & dance number to rambo-ing his way out of a basement on fire with barely a hair out of place. In Detective Bureau 2-3 (1963), nothing looks real but everything is entertaining. True Suzuki spirit.

YOUTH OF THE BEAST (1963)

– THE HARDBOILED CLASSIC –

“Why do all you big shots say the same stupid lines?”

- Original Title: 野獣の青春

- Featuring: Shishido Jō, Watanabe Misako, Kawachi Tamio, Gō Eiji & more

- Studio: Nikkatsu

Perhaps hoping to repeat the formula of Detective Bureau, Nikkatsu soon tasked Suzuki with a very similar assignment: adapt another revenge and infiltration story by novelist Ōyabu Haruhiko, with Shishido in the lead role. However, the results could not have been more different, with a film as grim and hopeless as Detective Bureau was superficial and light-hearted. Mostly ignored by contemporary critics, the film was nonetheless of significance to Suzuki himself, who considered it his first original picture8.

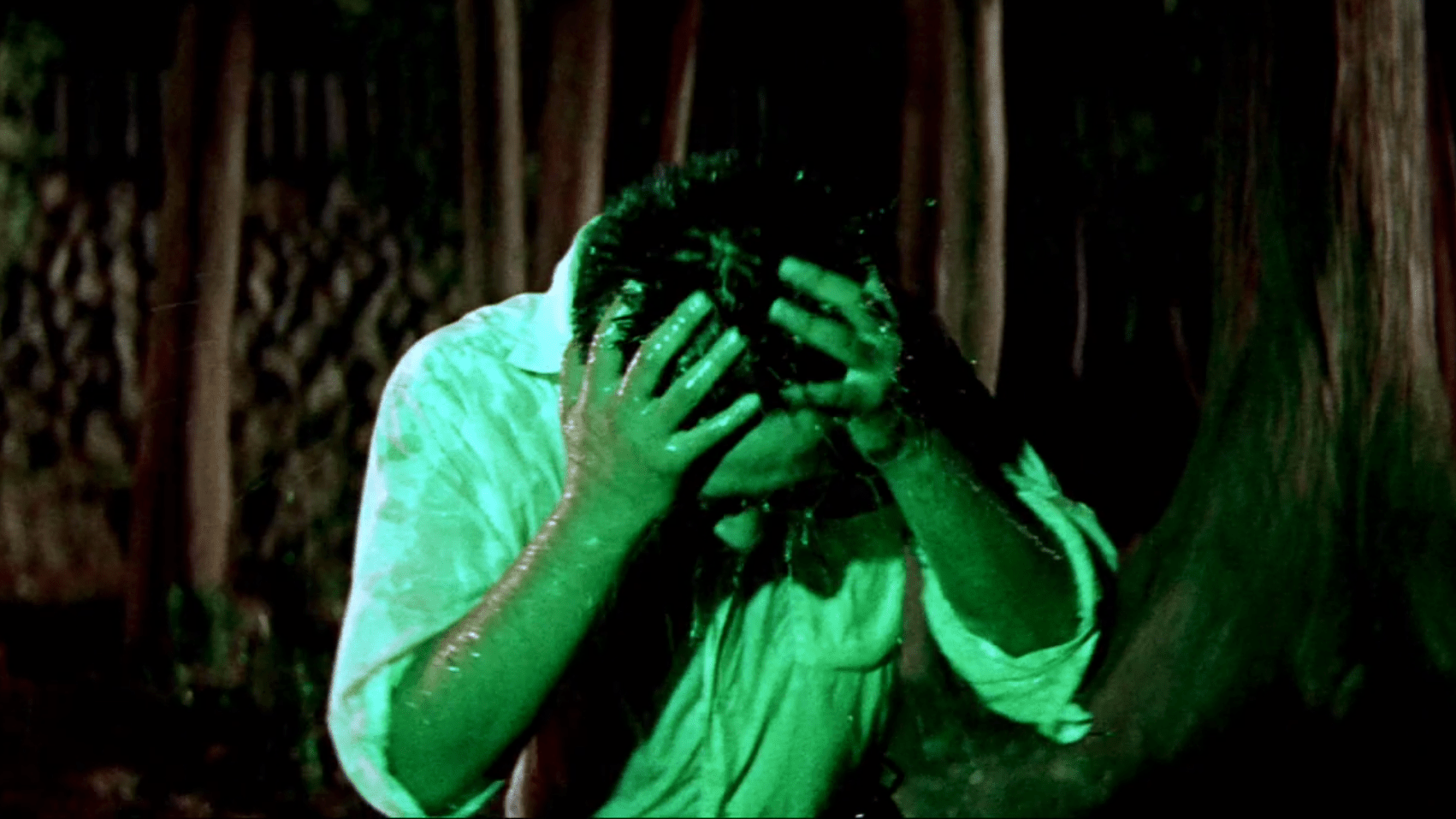

In the gritty Youth of the Beast (1963), Suzuki demonstrates that he is now in full control of his craft and style – and starts experimenting further. He goes beyond colour, playing with sound, cinematography, tone, and realism. A tragic scene filmed in black & white abruptly gives way to teenagers laughing in extra-saturated colour. A character pauses to watch a film in the background. Torture scenes real or imagined are thrown at the viewer before being put away like a bad dream. And in between, non-sequiturs and self-referential, immersion-breaking scenes only add to the viewer’s unease, with the typical noir story of betrayal going to unexpected places. A film as brutal as it is unforgettable, Youth of the Beast (1963) is an fascinating early sign of what was to come in Suzuki’s work.

TOKYO DRIFTER (1966)

– THE POP MASTERPIECE –

“Money and power rule now. Honour means nothing!”

- Original Title: 東京流れ者

- Featuring: Watari Tetsuya, Nitani Hideaki, Matsubara Chieko, Kawachi Tamio, Gō Eiji & more

- Studio: Nikkatsu

Moving on from noir and detective films, 1963 saw Suzuki make his first foray into ninkyo (chivalrous yakuza films) with the visually striking Kanto Wanderer (1963) and The Flower and the Angry Waves (1963), featuring Diamond Guy Kobayashi Akira. Suzuki’s most successful film at Nikkatsu, Gate of Flesh (1964), soon followed, led once again by Shishido as a hostile WWII veteran. But despite his creative successes, all was not well for Suzuki, whose excentric flourishes and forays into surrealism greatly displeased the pragmatic Nikkatsu studio executives, earning him increasingly regular warnings9.

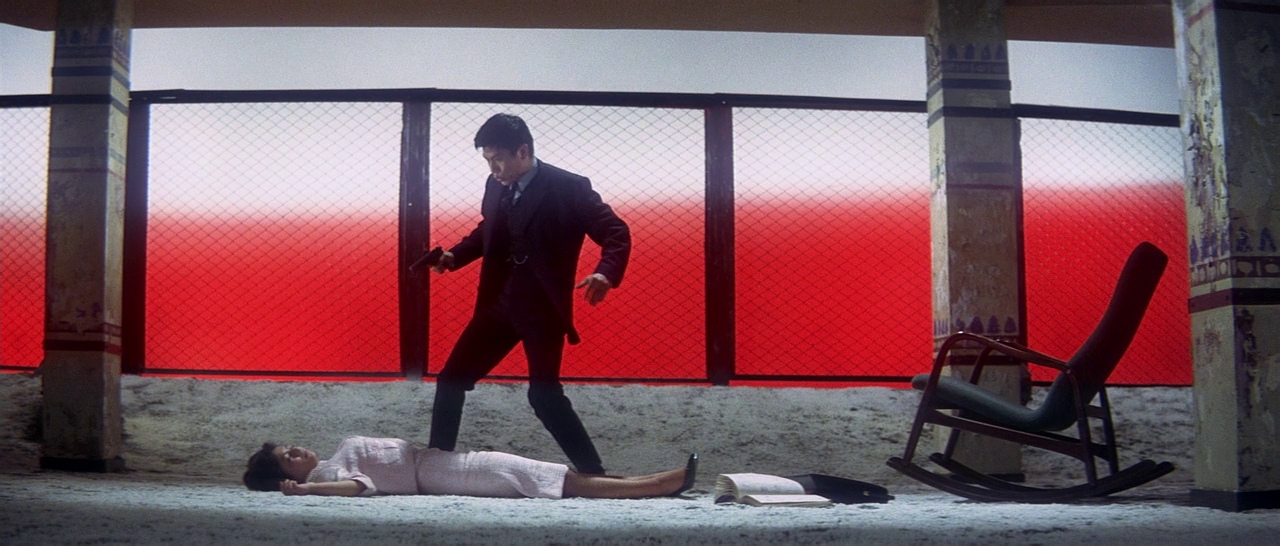

Undeterred and unbothered, Suzuki built on elements from these all of these films to direct his most overtly theatrical film yet: Tokyo Drifter (1966). Suzuki elevates the stereotypical yakuza/ninkyo story with bold visuals and cinematography, taking every opportunity to delight the eye and surprise the viewer. Opening in black and white once more, the film quickly bursts into vibrant colours, carrying on the wild technicolour spectacle until the very end. Colour-coded characters return from Gate of Flesh (1964), playing into their archetypal nature, and the kabuki-like scenes return from earlier Suzuki ninkyo. The timeless masterpiece would once again gain cult status in years to come – but, on completion, Tokyo Drifter (1966) marked the beginning of the end for Suzuki at Nikkatsu.

BRANDED TO KILL (1967)

– THE PSYCHEDELIC CODA –

“A killer mustn’t be human.”

- Original Title: 殺しの烙印

- Featuring: Shishido Jō, Mari Annu, Nanbara Kōji, Ogawa Mariko & more

- Studio: Nikkatsu

Tokyo Drifter (1966) enraged the Nikkatsu executives, frustrated by Suzuki’s increasingly abstract and provocative output at a time when they needed straight hits. Forced to release the disavowed film due to scheduling constrains10, they issued one final warning to Suzuki and took away his colour-film privileges, premusably hoping to put a physical curb on his expansive style once and for all. After the relatively tame Fighting Elegy (1966), and due to Nikkatsu’s increasing struggle to keep afloat, Suzuki found himself in the surprising position of having one of his team’s proposal greenlit, with the studio desperately needing a quick release for cash flow11. That film, ordered to be shot in black & white again and with a lead also in trouble in Nikkatsu, was Branded to Kill (1967).

Suzuki, surprising nobody, disregarded Nikkatsu’s warnings and leveraged the new constraints to direct a film that would blow apart all the historical conventions of Nikkatsu productions. Visually striking, multiplying extravagant sets, incongruous theatrics, unusual cinematography, and even full nudity; exploring death, dark obsessions, and fetishes; disorienting the viewer with nonsensical plot points and plenty more non-sequiturs; and featuring a magnetic cast, explosive in daring scenes that few had attempted at Nikkatsu in 1967. The feverish Branded to Kill (1967) would eventually reach cult status, but in 1967 the film was a total commercial and critical failure, ending the careers of both Suzuki (fired in 1968) and Shishido (demoted to support roles post-1967) at Nikkatsu, decisions that would have long-term impact on both.

We can only hope that Suzuki and Shishido both found some relief in seeing the film, and their work in general, gain incredible international fame and appreciation all these years later.

WHAT ABOUT MORE OTHERS / MODERN SUZUKI FILMS? 🤔

The Suzuki films mentioned throughout this list all merit a viewing, further emphasising Suzuki’s breadth and style evolution throughout the 1960s.

Post-Nikkatsu, Suzuki fortunately returned to the director’s seat in 1977, and released the acclaimed Taishō Trilogy from 1980 (Zigeunerweisen (1980), Kagero-za (1981), Yumeji (1991)), which will be of interest to Suzuki enthusiasts.

Notes and References

1. Suzuki, Seijun (January 1991). “Mijn werk—My Work”. De woestijn onder de kersenbloesem—The Desert under the Cherry Blossoms. Uitgeverij Uniepers Abcoude. pp. 27–31.

2. Suzuki entered the profession at Shochiku studios after failing Tokyo University exams, was a self-professed unproductive and unmotivated assistant director, and entered Nikkatsu in 1954 to triple his salary, eventually becaming a director in 1956. As reported in: Suzuki, Seijun (January 1991). “Mijn werk—My Work”. De woestijn onder de kersenbloesem—The Desert under the Cherry Blossoms. Uitgeverij Uniepers Abcoude. pp. 27–31.

3. Coined in February 1960, the Diamond Line consisted of Ishihara Yujiro, Kobayashi Akira, Akagi Keiichiro, and Koji Wada. After Akagi’s tragic death in 1961, Shishido Jo would be added to the line-up updated to ‘New Diamond Line’.

4. As reported by the Embassy of Japan – Washington DC in Action, Anarchy, and Audacity: A Seijun Suzuki Retrospective, https://www.us.emb-japan.go.jp/jicc/events/seijun-suzuki.html, (accessed 22 May 2023).

5. Shishido, Jō. Interview. Conducted by Mark Shilling for “No Borders No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema”, Fab Press, 2007. p. 95.

6. Shishido, Jō (2007). Interview. Conducted by Mark Shilling for “No Borders No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema”. Fab Press. p. 87.

7. Rayns, Tony (1994). “The Kyoka Factor: The Delights of Suzuki Seijun”. Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun. Institute of Contemporary Arts. pp. 5–9.

8. D., Chris (2005). Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. I.B. Tauris. p. 136.

9. Suzuki, Seijun. Interview. Conducted by Chris D. for “Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film”, I.B. Taurus, 2005. p. 148.

10. Suzuki, Seijun. Interview. Conducted by Mark Shilling for “No Borders No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema”, Fab Press, 2007. p. 102.

11. Carroll, William (2022). Suzuki Seijun and Postwar Japanese Cinema.Columbia University Press. p.193.

Discover more from Gamblers & Drifters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “5 Films to Explore Suzuki Seijun”